Place in the world

As I walked into the British Museum's 'Burma to Myanmar' exhibition I spotted a woman who looked as if she was of Burmese descent talking to a couple (at least one of whom was not of white British descent) about the infamous 'golden letter'.*

A man who looked very much like he was of white British descent walked up and asked whether it was a guided tour. The woman apologised and said it was a private tour. He asked whether he could have a private tour, and in the graceful polite manner I remember from my visit to Burma, she said, 'The exhibition ends this weekend. I'm sorry.' He rounded on her and said aggressively, 'Why are you sorry?' then turned his back.

I was acutely embarrassed. I am white British. I have history. Never let racism pass.

I said to the threesome, 'I apologise for that rudeness,' and, as I learnt in Myanmar, bowed my head slightly.

Immediately they asked me to join their group. I thanked them but said I wouldn't disturb them and went on to look at the first case.

My complicated, layered relationship with Burma started well over 50 years ago when my dad wouldn't talk about his time there in the Second World War. But 40 years ago, when I joined the British Council and was made the London-based desk officer for Burma, he was fascinated by what I was doing and opened up. He told me that as a Royal Engineer he had had a much easier time there than many had had. He was building bailey bridges and wasn't on the infamously brutal front line.

In my work I met several Burmese people and couldn't match their gentle grace with the horror that I knew of Burma in the 1980s: of dictatorship, repression, lifelong political imprisonment and state murder. Even the people from the embassy, who you'd expect to echo their brutal government, exuded kindness and calm. I was puzzled and intrigued and desperate to visit. But although I visited the other countries I was 'responsible' for (Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal) the British Council didn't think it was safe for me to visit Burma. One of my specialist colleagues, though, was sent to look at English language teaching in Burma and to recommend how the British Council should support it. He got back even more tangled by Burma than I was and, as deadlines crashed around him, it took the two of us together to coax his reactions and recommendations onto paper.

So when, at the far end of the first exhibition case, I read that the artefact on display had been presented to the British Museum by him many years later when he returned from being British Council Director of Burma (I hadn't known that he'd manoeuvred himself into that post) yet another twist was added to my Burma story. At that point the group of three and I found ourselves together and the man who'd invited me to join them told me that the Burmese woman was the curator of the exhibition. From then on I moved at about the same pace as them, sometimes listening to her and asking questions and sometimes leaving them alone. What an extraordinary privilege!

From the title of the exhibition, I'd been expecting a stronger thread about how the tribal states in the area that is now Myanmar had been 'united' as 'Burma' under the 'India' bit of the British Empire then made into an incoherent state at independence, leading to the political chaos that has characterised the country since. In fact, it was much stronger on artefacts and culture, with the tribal and political history being told around the edges. But it ended with a video of some of the many protests against repression that the unbelievably brave people of Myanmar organise from time to time. I watched that through three times.

Pictures

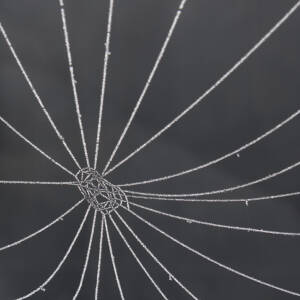

Main: I don't know whether my dad ever had one of these silk maps of Burma, issued in the early 1940s to help Allied soldiers escape if they were captured. Strong, waterproof, easily concealed and silent in use.

Extra 1 - A mother-of-pearl inlaid Buddhist text in one of the extraordinarily 'cursive' scripts of central Burma (1770-1850)

Extra 2 - leaving the British Museum

* The Golden Letter, a manuscript in Burmese written on rolled gold edged with rubies, was sent in 1756 by influential King Alaungpaya of Burma to King George II in London offering expansion of the longstanding trade relationship between the two countries. To avoid misinterpretation, a translation was sent with the original letter but, despite this, when it arrived in London, after a two-year journey, George II and his court understood neither the contents nor the significance of the message and saw no reason to respond. He sent it to the library in his home city of Hanover without ever acknowledging receipt let alone replying to King Alaungpaya who felt seriously insulted. The letter was then 'lost' (although there were transcripts) and only when it surfaced in 2013 was its significance recognised.

Black and white in colour 283

Comments

Sign in or get an account to comment.