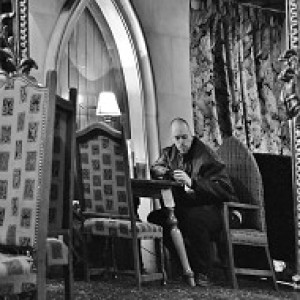

1913

It's been a hundred years now since this photograph was taken, and sadly, there's been little attempt locally to commemorate the story behind it, or tell the tale to a new generation of how the ordinary people of the Black Country found it in themselves to take on those who sought to exploit them, and won. It was always unlikely to happen while the local newspaper insists on prioritising letters sent by Enoch Powell worshippers, and the BBC - on both a regional and national level - runs scared of anyone who accuses it of "left wing bias" (or, as it's otherwise known, "telling the truth").

The conservatards of the world would have everyone believe that Britain between 1910 and 1914 was a utopia in which everyone was chuffed with their lot; happy to doff their cap to anyone with a slightly poncier name, and eager for the First World War to kick off so they could take part in the nationwide competition to win a free picture of the king for every 50 machine-gun bullets they collected inside their body. In fact, it's a wonder why newspapers at the time called the era "The Great Unrest", given that everything in Edwardian society was obviously so hunky-dory. And as for the government stationing a warship in the river Mersey during a dockers' strike; well, you have to find some way of supervising Scousers on holiday, don't you?

In fact, during those four years, folk across Britain fought at different times in different regions to try and earn a decent standard of living, taking their lead from each other's example. In summer 1913 it was the turn of Black Country workers, long referred to as "the white slaves of England". The average working week in the area was 55 hours, and the average weekly wage 19 shillings; equivalent, in terms of buying power, to just under £40 in modern currency. Inflation had raised the price of food by 10% since 1907, but wages in many industries had decreased due to a slump in trade. Over 53,000 people a year died from tuberculosis alone within the area, with greater numbers suffering from illnesses relating to malnutrition. When the unions called for action and the people responded, they weren't demanding a palace for every employee or a workers' council within each factory; all they asked for was a minimum wage of 23 shillings a week. That increase would, in modern terms, have given them a buying power equivalent to an extra £15 pounds or so each week. Enough for a rich man to buy a Charlie Chaplin DVD or the MP3 album of Fuzzy-Wuzzy Fraser Sings Jingoistic Music Hall Hits, Vol 1. But, for your average labourer round these parts, that money had the power to save lives.

The first men out were employees of Tangyes Engineering Works in Smethwick - the company whose machinery had installed Cleopatra's Needle in London, and would in future go on to facilitate the construction of Sydney Harbour Bridge, Spaghetti Junction and the Thames Barrier. Soon after, strikes were declared by the men of the Birmingham Carriage Works and the London Screw Company. Atlas Nut & Bolt Works in Darlaston followed suit, along with Stewarts and Lloyds Tube Works in Halesowen and Russells Old Patent Tube Works in Wednesbury. 30,000 men were on strike. Police were required to escort blacklegs to work at the Jubilee and Sandwell Park collieries in West Bromwich. There was no such thing as strike pay; those workers out had to rely on donations to feed their families, and undertook marches to raise funds, including one walk that went for 280 miles via Manchester and Liverpool in 16 days.

Newspapers described "much rowdyism" at demonstrations (why can people standing up for their basic rights as human beings never do it quietly, eh?) and the employers spoke of "gross intimidation" and "the beginnings of a reign of terror" (yes, these destitute men and their starving, tuberculotic offspring were really bang out of order in making the top hat brigade uncomfortable, weren't they?) But in spite of their babblings and bleatings, the employers were brought to the negotiating table. A joint conference between masters and men voted on satisfactory terms for all: a 23 shilling minimum wage, standardisation of rates for youths and girls, and recognition of the right to membership of trades union by all employers.

According to minutes, the conference concluded: "Let us hope that the settlement which ended the strike may prove the beginning of happier days, and that in the relations between the employer and the employed there will be manifested in the future the spirit of goodwill, justice, honour, and respect from each to the other." Well, that's very much a work in progress, isn't it? What a wonderful world it would be if we could achieve that ideal, on terms that were acceptable to both parties, and sensible negotiation possible on difficult issues. But until that time comes around, it's down to us to keep stories like the 1913 Black Country strike alive, and not let it be swept under the carpet by those who want to sanitise history for their own purposes.

After all, what these people excel at is making us our own worst enemies. And believe me, there are far better worst enemies out there.

- 0

- 0

- Nikon D3100

- 1/33

- f/5.6

- 55mm

- 1400

Comments

Sign in or get an account to comment.